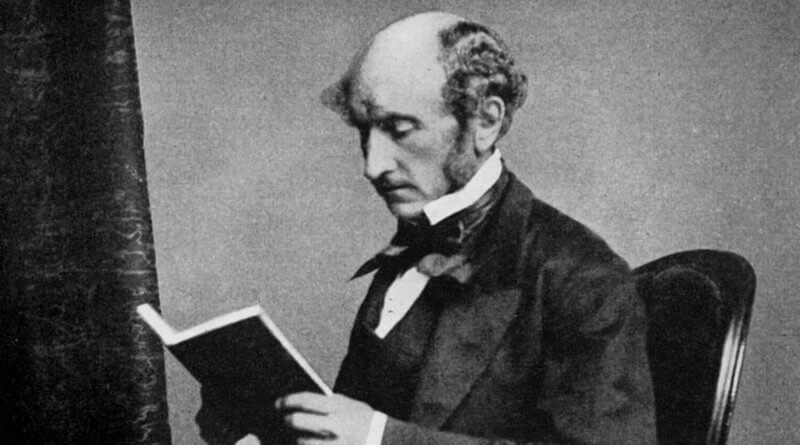

A Defense of Mill and the Principle of Utility

John Stuart Mill illustrates the Principle of Utility as a guide for individual action in which morality is determined by the consequences of an action, rather than the motives behind it. If the consequences of an action promote happiness (pleasure) and do not promote pain, then the action is ethical. However, Bernard Williams criticizes Utilitarianism for jeopardizing personal integrity with the intention of giving equal importance to the happiness of people outside of the individual.

Utilitarianism, by definition, may also seem either unrealistic to some due to its rejection of completely self-interested action, or too lax for leaving room for improvements. Though Utilitarianism is criticized for an “unintelligible” view of integrity and an unreasonable standard for human action, Mill’s Principle of Utility remains clear and applicable by upholding the significance of individual action and allowing for improvement over time.

Williams’ defines integrity, or an “idea closely connected with the value of integrity,” as the principle that “each of us is specifically responsible for what he does, rather than for what other people do” (Singer 69). Utilitarianism upholds this principle simply by being an ethical theory that proposes a guide for individual action. Though Utilitarianism promotes happiness for all, the theory itself is designed to guide individual action, with each action having weight according to its impact on general happiness. According to Utilitarianism, when a person is choosing between an action that promotes their own happiness and an action that promotes the happiness of others, the person should be completely objective and choose the action that promotes the most happiness overall (Mill 28).

Williams argues that this need for complete objectivity undermines personal integrity (Singer 69). However, according to Williams’ own definition, it is integrity that allows an individual to make such a decision. Integrity, or the sense of responsibility for one’s own actions, allows a person to make a decision that promotes the most happiness, rather than making a selfish choice just for the sake of being selfish, or a completely selfless choice just for the sake of being selfless.

Williams uses the example of George and the biological warfare job to further illustrate the issue of personal integrity under Utilitarianism. In this example, a man named George is in dire need of a job. His friend informs him that a job is open at a research facility that specializes in chemical and biological warfare. On a personal level, George is ethically opposed to this kind of research. However, he needs a job to provide for his family, and George’s friend also informs him that another man, who will likely get the job if George declines, is “not inhibited by any such scruples and is likely if appointed to push along the research with greater zeal than George would” (Singer 68). So what should George do? According to Utilitarianism, he should take the job. It would promote the most happiness for the group of people (family, friends, etc.) for which George’s actions have a direct impact.

According to Williams, this is not necessarily the right choice because it does not take George’s personal integrity regarding biological weapons research into consideration (Singer 69). However this seems to be very weak reasoning at best. Assuming that, after deep deliberation on the matter, George did take the job, his personal integrity would have to play a role in the decision-making process. Under Utilitarianism, one must weigh the consequences objectively, but that does not mean that one does not consider one’s own beliefs when making a decision. It simply means that an individual should not give those beliefs precedence over the happiness of others. In the end, the decision to take the job would promote the most happiness for those people whose happiness is directly impacted by the decision, and would therefore be ethical.

One criticism of Utilitarianism is the steadfast regard for the happiness of others, and how this ideal is unreasonable for most humans to live by. However, Utility does not propose a strict rule for living an ethical life, but rather an encouragement to promote happiness whenever possible. When circumstances arise that force an individual to decide between his own happiness and the happiness of others, the individual must make an objective decision. While objectivity may be difficult, it is not impossible. Mill is not suggesting that we always act with complete objectivity in every situation, but rather we should try to be objective regarding ethical issues as much as we can (Mill 37).

For example, let us assume that there is a man named John who is suddenly confronted by an attacker on the street. The attacker has a gun and intends to kill John. John has no family and few friends, but he wants to stay alive. The attacker has several children and wants to take John’s wallet so he can feed his family. In this situation, it would theoretically promote the greatest amount of happiness if John allowed the attacker to kill him and take his wallet. However, John instinctively tackles the man, takes the gun, and runs away. Within a very strict, finite view of Utilitarianism, John made the wrong decision. However, allowing for “peculiarities of circumstances” (as Mill suggests), John’s decision is at the very least ethically neutral (Mill 37). John made a snap decision to give his own happiness precedence over his attacker’s happiness in a life-or-death situation. This scenario is exemplifies the ease of practice and the malleable nature of Utilitarianism.

Though I have answered the criticism that Utilitarianism is too unreasonable to practice, this allows for questioning its strength as an ethical theory. Is Utilitarianism too lax? Does admitting the need for improvement render Utilitarianism useless? On the contrary, leaving room for improvement is actually one of Utilitarianism’s greatest strengths. Ethics has changed greatly over time. Social practices have changed, ethical theories have evolved, and new ethical theories have been produced. Today, an individual’s actions impact far more people now than they did a thousand years ago. So why should we assume that our ethical views today are the absolute best that they could ever be?

Allowing for improvement only strengthens the Principle of Utility. Rather than being a strict, unmovable set of rules to live by, it is a malleable framework on which changing values can be placed and restructured. This is also a feature that most ethical theories enjoy. Mill states “there is no ethical theory which does not temper the rigidity of its laws by giving a certain latitude, under the moral responsibility of the agent, for accommodation to peculiarities of circumstances” (Mill 37). By allowing for change, Mill is ensuring that Utilitarianism stands the test of time as a legitimate ethical theory.

The Principle of Utility is rather simple in its basic tenets, and it is this feature that makes it an easy target for criticism. Bernard Williams sees the use of objectivity as a slight to personal integrity. Other critics believe the entire theory is too strict, while some believe it is not strict enough. In actuality, it answers all of these criticisms and strikes the perfect balance between strength and variability. It does this by promoting the importance of objectivity when determining which actions to take, while also allowing for improvements to be made as time goes on and social values change. It also incorporates personal integrity by allowing integrity to be a natural part of decision-making when ethical dilemmas arise. I believe that these characteristics illustrate the strength of the Principle of Utility, and help ensure that it will be a long-standing theory for ethical practice.

Want to see more essays and reviews about Film and Philosophy? Click here to keep reading!

Sources:

Mill, John S. Utilitarianism. New York: Prometheus, 1987. Print.

Singer, Peter. Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 1994. Print.