10 Surrealist Films for Philosophy Students

What is a Surrealist Film?

Defining “surrealism” or “surrealist films” is no simple task. That said, Andre Breton’s writings provide a definition and overview of the surrealist movement. In his landmark work, Manifesto of Surrealism, Andre Breton lays out an argument in favor of surrealism, primarily as a means of living and thinking, one which is radically different from our typical, day-to-day mental processes. Much of what Breton opposes is the under-appreciation (or even outright dismissal) of dreams and the bewildering nature of thought, as well as our blind adherence to rationality. He believes that we continue to live under “the reign of logic,” and that the “absolute rationalism that is still in vogue allows us to consider only facts relating directly to our experience.” In his own way, Breton is essentially condemning close-mindedness, and does so by making the claim that it is not merely a defect of the ignorant, but a pervasive quality of the entire human race. He takes this a step further, stating that “under the pretence of civilization and progress, we have managed to banish from the mind everything that may rightly or wrongly be termed superstition, or fancy; forbidden is any kind of search for truth which is not in conformance with accepted practices.”

While Breton never lays out clear instruction for how one may rid themselves of the traditional modes of reasoning and embrace the surreal, he does provide insight into what is meant by the surreal, and specifically how it differs from rationalism. Breton remarks that the “ordinary observer lends so much more credence and attaches so much more importance to waking events than those occurring in dreams,” though in a state of lucidity, man is at the mercy of his own memory, a memory which “takes pleasure in weakly retracing for him the circumstances of his dream, in stripping it of any real importance.” This concept of waking thought being grossly inferior, while simultaneously much more accessible to us is integral to Breton’s hypothesis. We embrace these thoughts and poorly-conceived memories out of habit, and shun our dreams and ephemeral visions for failing to integrate coherently with our usual methods of thought. Breton ultimately concludes that our waking state is nothing more than a “phenomenon of interference.”

So, what is it about dreams that Breton finds so superior to rational thought? In part, it is the abandonment of unnecessary limitations. He summarizes this view with the following:

“The mind of the man who dreams is fully satisfied by what happens to him. The agonizing question of possibility is no longer pertinent. Kill, fly faster, love to your heart’s content. And if you should die, are you not certain of reawakening among the dead? Let yourself be carried along, events will not tolerate your interference. You are nameless. The ease of everything is priceless.”

However, Breton does not completely condemn the waking state. In fact, it is as necessary as the dreaming state, if only as a way to analyze and reform dreams. It is the resolution of these two states that he describes as “surreality,” which is, to Breton, the highest and most absolute reality. Breton continues, providing two more precise definitions for surrealism, one as it relates to functions of the mind:

“SURREALISM, n. Psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express — verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner — the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by the thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.”

…and the other as it relates to a philosophical school of thought:

“[SURREALISM]. Philosophy. Surrealism is based on the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of previously neglected associations, in the omnipotence of dream, in the disinterested play of thought. It tends to ruin once and for all all other psychic mechanisms and to substitute itself for them in solving all the principal problems of life.”

All of this leaves us with a roadmap for interpreting and categorizing surrealist films as being distinctly surreal. Using Breton’s definitions as a basis, it is evident that a Surrealist film must, in one way or another, produce a combination of images, sounds, words, and even concepts that are either a reproduction of a dream state or a reflection of the natural state of human thought. As it pertains to images (in any art form), Breton takes from Baudelaire in stating that “it is true of Surrealist images as it is of opium images that man does not evoke them; rather they ‘come to him spontaneously, despotically. He cannot chase them away; for the will is powerless now and no longer controls the faculties.’”

It is important to note the difference between films that include surreal imagery, and productions which may be called surrealist films in the abstract sense. Many films include “dream sequences” that are, by definition, surreal, but once these scenes are finished, the films return to traditional forms. This list is more concerned with films that maintain a certain degree of surrealism throughout. This can be achieved in a variety of ways; films can evoke surrealist concepts through content, form, or a combination of the two. With this in mind, a certain list of qualities, however broad in scope, come to mind when envisioning a surrealist film. The films on this list all possess more than one of the following characteristics:

- A narrative structure that does not conform to the normal Hollywood or even European traditions; the story may be disjointed, repetitive, or include the juxtaposition of seemingly unrelated narrative elements.

- The film includes an interpretation of the functions of the mind, whether it is stated outright or through cinematic effect; this might include images that blend into one another, brief intrusions of sounds or visions, or dream-states that offer little or no ostensible narrative significance.

- Images, characters, or dialogue that transcend what we know to be normal or real; this could include fantastical creations that cannot be seen in the real world, absurd or indecipherable languages, or behavior from humans or creatures that seems incompatible with their nature.

- An indifference to practical sense; any aspect of the film may be either counterintuitive or simply irreconcilable with rational thought.

While this is by no means a comprehensive list, the following surrealist films all adhere to the characteristics as they have been described.

10 Surrealist Films for Philosophy Students

10. The Holy Mountain (Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1973)

In Jodorowsky’s followup to El Topo, a man (simply referred to as The Thief), embarks on a journey of self-discovery and spiritual awakening. He is joined by The Alchemist (played by Jodorowsky himself) and seven superior beings that have all come from different planets to discover the secret to immortality. Rich with symbolic imagery and sequences that mix dreams and reality, The Holy Mountain infuses Jodorowsky’s own beliefs with the psychedelic aesthetic of 70’s cinema. You can find my review of the film here.

The Holy Mountain is available to rent or purchase via Amazon here.

9. Last Year in Marienbad (Alain Resnais, 1961)

At a remote château, a woman is approached by a man who claims to have met her a year prior, though the woman denies it. A second man attempts to emasculate the first man, though the reasons are not entirely clear. Scenes jump in time and space, with images often disconnected from the larger story. The entire film feels like a half-remembered dream, with segments that are hazy or simply cut short. There is no sense of beginning or end, but rather a continuation of dissociative sequences that form a contemplative, but nonetheless incomprehensible whole.

Last Year in Marienbad is available to rent or purchase via Amazon here.

8. Inland Empire (David Lynch, 2006)

David Lynch is known as a master of the surreal, and this is exemplified in his strange and unsettling drama, Inland Empire. The story follows an actress named Sue who lands the lead role in a film, but the film’s production is plagued by strange occurrences, and Sue is further disturbed by a strange woman claiming to know about future events in her life. Lynch plays with the concept of time, and, as is so often the case in his films, the characters are enigmatic and behave in a cryptic manner.

Inland Empire is available to purchase via Amazon here.

7. House (Nobuhiko Obayashi, 1977)

The only horror film to be on this list, House tells the story of Gorgeous, a young girl who goes to visit her aunt with six of her friends. When they arrive, supernatural happenings and demonic possessions force the girl’s to fight for their lives as they attempt to discover the secrets of the house. Not only is the imagery strange (and often shifts between horrific and comedic), but the story follows a dream-logic that offers little justification for the fantastic and frightening occurrences.

House is available to rent or purchase via Amazon here.

6. Meshes of the Afternoon (Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid, 1943)

This experimental short, brought to life by real-life husband and wife Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid, is more a collection of images than it is a singular film. There is no sense of time or continuity in the narrative, only the a repetition of images to give the film a sense of meaning that is open for interpretation. Much like dreams, we only get flashes of objects and surroundings, giving us an impression of events, rather than a direct view. Though there is little in the way of a cohesive narrative, the film generally follows a woman as she tries to catch a hooded figure and distinguish between her dreams and reality.

Meshes of the Afternoon is available to stream via Amazon here.

5. Daisies (Věra Chytilová, 1966)

Czechoslovakian filmmaker Věra Chytilová directs this tale of two young women, Marie I and Marie II, who embark on a series of pranks and peculiar misadventures. Though the two show a proclivity for overeating and general misbehavior, there is little coherence that can be drawn from the characters or the narrative. We watch as the two drift among different scenarios, being swept onward by the absurdity of the setting.

Daisies is available to purchase via Amazon here.

4. Persona (Ingmar Bergman, 1966)

As can be surmised from the title, Persona is a film largely about identity, specifically identity insofar as it is an abstract concept, both difficult to define and capricious by nature. In the film, Elisabet is an actress who is suddenly unable to move or speak, and is left under the care of a nurse, Alma. On doctors orders, Alma takes Elisabet to a cottage by the sea. As Alma tells Elisabet various stories from her life, their relationship becomes increasingly complex and their identities seem to blend into one another.

Persona is available to rent or purchase via Amazon here.

3. Amarcord (Federico Fellini, 1973)

Loosely based on people and events from his own childhood, Fellini’s Amarcord is a comical denunciation of Mussolini’s fascist regime. It features a wide array of character archetypes, ranging from the village idiot to the local nymphomaniac. Much of the story focuses on Titta (based on Fellini himself), and his comical interactions and observations of the other villagers. The narrative meanders between various sequences, giving spectators a strange and satirical view of Italy under fascism.

Amarcord is available to rent or purchase via Amazon here.

2. Naked Lunch (David Cronenberg, 1991)

Adapted from the works of William S. Burroughs, Naked Lunch follows William Lee, an exterminator turned writer who becomes entangled in a conspiracy surrounding illegal narcotics. William, as well as several other characters, are frequently under the influence of hallucinatory drugs, making it difficult to distinguish between their visions and reality (if such a distinction even exists). Little of Naked Lunch’s plot can be justified as a coherent chain of cause-and-effect, and the anthropomorphic beings are treated as relatively normal occurrences within the narrative world.

Naked Lunch is available to purchase via Amazon here.

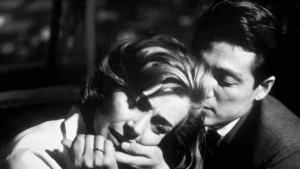

1. Hiroshima Mon Amour (Alain Resnais, 1959)

Though it is a love story, Hiroshima Mon Amour is primarily a study on memory and reflection, framing its narrative as a series of cryptic conversations and visions of the past. Through several documentary-style sequences, the characters (simply referred to as Her and Him) compare the death of their relationship with the bombing of Hiroshima. The film’s dialogue, which is often repetitive and ambiguous, is juxtaposed with images that reflect the transient nature of memories and human emotion.

Hiroshima Mon Amour is available to rent or purchase via Amazon here.

Surrealist Films, Honorable Mentions:

8 1/2 (Federico Fellini, 1963)

Mulholland Drive (David Lynch, 2001)

Lost Highway (David Lynch, 1997)

Repulsion (Roman Polanski, 1965)

If you have any other surrealist films that you think should have been included, feel free to leave a comment!

Sources:

Breton, Andre. “Manifesto of Surrealism.” Jstor, College Art Association, Nov. 1971, www.jstor.com.