Trainspotting Analysis: The Dilemma of Scottish National Identity

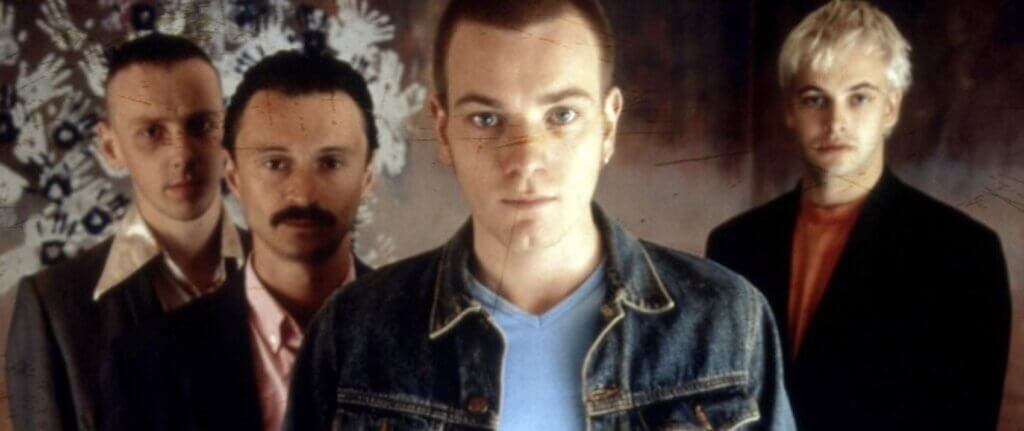

Trainspotting, a film by director Danny Boyle, follows the misadventures of a group of Scottish heroin addicts in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s. The film is narrated by one of the young addicts, Mark Renton, who struggles between staying loyal to his dysfunctional friends and parents and attempting to stay in control of his crippling addiction. This Trainspotting analysis will look at the film from a cultural perspective, while also analyzing the various relationships portrayed through its episodic narrative and frenetic visual style. Though many of the narrative and aesthetic qualities of the film can be described as distinctly Scottish, this description is problematic.

Scotland’s history and culture is one that is uniquely defined by outside forces, so much so that the word “Scottish” is more closely associated with those outside forces than with Scotland itself. A combination of historical and cultural factors have, over time, created a lack of national identity in Scotland. The oppressive rule of the English has been prevalent in Scotland since the early 18th century. More recently, Scottish identity has been defined by the continued economic and political dominance by the English, and the all-pervasive influence of American pop culture. The narrative and visual style of Trainspotting are both reflections of the history of colonialism and the influence of American pop culture in Scotland.

A Brief History of Scottish Representation

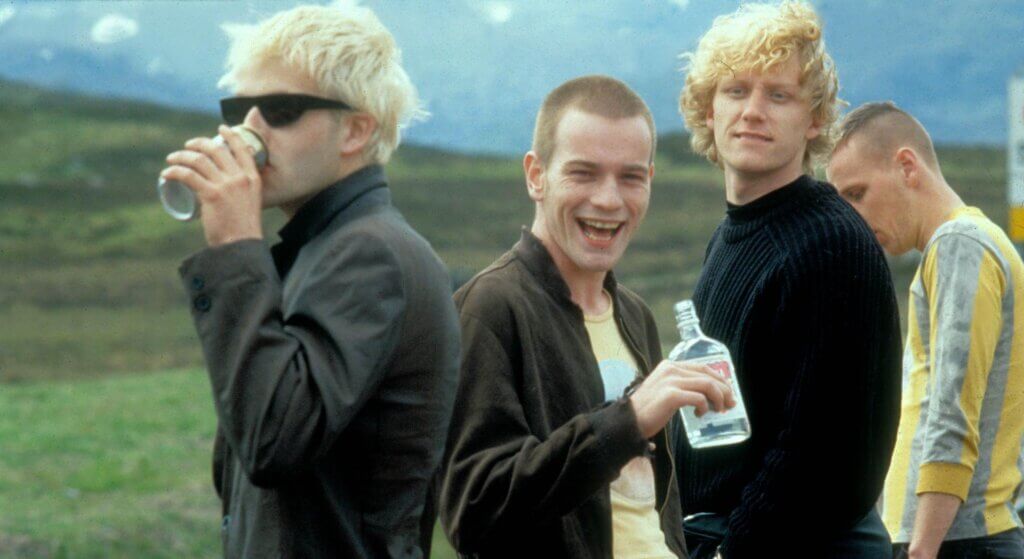

Since the inclusion of Scotland into Great Britain in 1707, Scotland has been under the unofficial rule of the British (Smith 9). Though some Scottish citizens were in favor of joining Great Britain, many Scots (particularly in the Highlands) fought back with little success. In the decades following this new union, a global image appeared depicting the Scots as a “rural, cozy, easy going people” (Thomsen, “Scottish Nationalism”). However, the Scottish people have actually been in a state of quiet dissatisfaction that only worsened with the onset of rebellious youth and countercultures in the 70’s, 80’s, and 90’s. This “dissenting grumbling” is most evident in Trainspotting (Thomsen, “Scottish Nationalism”). For example, when one of Mark’s friends (Tommy) gets dumped by his girlfriend, he takes the gang out to the Highlands for no apparent reason. Looking at the beautiful landscape, Tommy asks his friends, “doesn’t it make you proud to be Scottish?” To which Mark replies:

“Its shite being Scottish! We’re the lowest of the low. The scum of the fucking Earth! The most wretched, miserable, servile, pathetic trash that was ever shat into civilization. Some hate the English. I don’t. They’re just wankers. We, on the other hand, are colonized by wankers. Can’t even find a decent culture to be colonized by. We’re ruled by effete assholes. It’s a shite state of affairs to be in, Tommy, and all the fresh air in the world won’t make any fucking difference!”

Mark’s friends have nothing to say to this, but collectively decide to go home and get back on heroin. Mark’s speech perfectly summarizes the Scottish view of colonization. While Mark states that he does not actually hate the English, he shows his frustration over the “shite state of affairs” that Britain has allowed the Scottish to fall into. The reaction to his speech is just as significant. Tommy, Sick Boy, and Spud say nothing because they agree with Mark, even if they are too afraid to admit it. And because the depressing nature of their situation is a hard thing to confront, they decide to use heroin to ease the pain.

» You Might Like: “The Matrix as Metaphysics” and Its Insignificant Implications

Many of the characters in Trainspotting also reflect the dissatisfaction with colonialism and the global image of the Scottish people. Mark, for example, is the perfect model of ambiguity and moral indifference. These characteristics echo the general traits of many Scots. Rather than actively trying to make his life better or rid himself of his “friends,” Mark chooses to passively accept his situation. He knows he wants happiness, he just does not know how to achieve it, so he turns to heroin.

He is neither sympathetic nor repugnant, and he is the flawed hero that most accurately represents the Scottish people: unhappy with his situation, but unwilling or unable to change it. Mark’s friend Spud is very similar in this respect. Though he is a much more sympathetic character than Mark, he too chooses heroin because he feels that he has nowhere else to turn. Tommy is the only character that represents the global view of the quintessential Scot. He is a kind, sympathetic, and passive character that helps reign in the antics of the rest of the gang. However, the film uses Tommy to disprove this enchanted image. Even though Tommy starts out as the most likeable character, he loses his girlfriend and suddenly his life plummets to the level of his friends. He chooses to use heroin and eventually dies due to complications with HIV.

The image of the “cozy, easy going” Scot is literally killed right before our eyes (Thomsen, “Scottish Nationalism”). Sick Boy and Begbie are the only central characters who do not directly reflect the Scottish people, but they do serve as the antithesis to Mark’s happiness, and in turn Scotland’s happiness. After Mark settles in London and finally feels as if he is “almost content,” Begbie shows up unannounced and moves in. Rather than being gracious, he belittles Mark and orders him to buy more cigarettes and beer. Soon after, Sick Boy shows up and moves in as well. He sells Mark’s television without permission, and gets Mark involved in an illegal drug deal to make some quick cash. They seem to reflect both Britain and the United States, with Begbie being the violent, bossy, over-bearing character (Britain) and Sick Boy being the sly, charming, greedy character (United States) that serve as barriers to Mark’s well-being.

Trainspotting and Scottish Politics

In the 1980’s and early 1990’s, the implementation of right-wing politics in Britain led to more liberal, even rebellious narrative themes in films like Trainspotting. The Conservative Party ruled Britain from the late 1970’s to the mid-1990’s, with Margaret Thatcher leading the most ideologically dominant movement of this period (Smith 9). Referred to as “Thatcherism,” this political movement supported a capitalistic free market economy and the “belief that people should take individual responsibility for the care of themselves and their families rather than relying upon state support,” which led to a reduction in government funds for “social services, health care, education and housing” (Stollery 56). At first there was a lot of resistance to Thatcherism, especially from the youth culture. However, the conservative agenda continued to be prevalent in Great Britain through the 1990’s, and opposition to it had dissipated greatly, leaving behind the disenchanted youth who, particularly in poorer areas, turned to drugs and crime in light of being politically ineffectual (Stollery 57).

Trainspotting puts particular emphasis on this political climate through the setting and indifferent attitude toward drug use. The film takes place in a particularly poor district of Edinburgh, the capital of Scotland. Rather than using the picturesque hills and valleys of the Northern Highlands, the film uses the backdrop of a gray metropolis to reflect the poor living conditions in the city that are a direct result of Thatcherism (Gardiner 89). Mark even makes a direct reference to Thatcherism when he states, “there was no such thing as society and even if there was, I most certainly had nothing to do with it.”

In this moment, Mark is referencing a speech in which Thatcher stated “there is no such thing as society. There are only individual men and women, and there are families” (Stollery 58). Besides referencing and showing the results of Thatcherism, many decisions made by the characters also seek to rebel against Thatcherism. At the start of the film, the characters choose not to participate in capitalist society. They reject the notion that a person needs to work to be able to buy certain luxuries.

Even though some of the characters are not altogether sympathetic, we are forced to sympathize with them in their struggle to find happiness. By only giving the audience Mark’s perspective, put within the context of his circumstances as a poor Scottish youth, we feel obligated to sympathize with his plight, whether or not his actions seem agreeable or justified. Therefore, we are forced to sympathize with his joblessness and drug use. The film is rebelling against Thatcherism just by portraying drug use and encouraging the audience to sympathize. Instead of being productive, obedient citizens, the characters in the film just use heroin. This is not only an unproductive hobby under the ideals of capitalism, but also illegal, and thus rebellious against the dominant conservative government.

While British dominance has served to oppress and frustrate the Scottish people, the intrusion of US culture has taken away their sense of national identity. American pop culture has become so prevalent in modern Scotland that a distinctly Scottish culture has become almost impossible to identify (Elsaesser 71). American trends, fashion, films, music and even politics have almost completely replaced any inherent Scottish culture that may have once existed. Trainspotting alludes to, and is also a victim of this cultural “takeover” in both its narrative and visual style. Even though the narrative has an episodic structure, which is more often a trope of European art cinema, the film uses certain key elements of the classical Hollywood narrative to appeal to international audiences.

The American Invasion

Mark, for example, is a protagonist who usually has clear goals. Even though some of his motives are ambiguous, overt psychological forces most often drive his actions. To break it down further, Mark’s psychological motives can be traced back to the cultural circumstances in which he lives. Mark resides in Scotland, which, due to the intrusion of American pop culture, lacks national identity. Therefore, Mark (as a Scot) wants to gain a sense of identity. Mark’s economic and social status are the direct results of colonialism and Thatcherism, exacerbating Mark’s frustration. Since he is a naturally passive person, rather than taking action to fix his situation, he turns to heroin. Once he starts using, his addiction drives him to get heroin at whatever cost. He then realizes that drugs do not solve his problems, and since his friends are just enablers, he must rid himself of them and start fresh. From beginning to end, the general motives for his actions are all coherent and plausible, much like a protagonist of the classical Hollywood cinema.

Trainspotting also shows its American influence through references to American pop culture. The character of Sick Boy is especially notorious for these references, particularly his references to James Bond and Sean Connery. While Sean Connery himself is Scottish, he became a huge film star in the United States (and everywhere else) portraying James Bond, a British secret agent. This use of a star that is a part of American, British, and Scottish pop culture strongly echoes the film’s global influences and the confusion of Scottish identity. Another star mentioned frequently is American punk rocker Iggy Pop. He is discussed in the film on multiple occasions, with his concert serving as a catalyst that inadvertently pushes Tommy to heroin. During the scene at the dance club, Mark stands by the wall directly in front of a painting of Robert De Niro’s character in Taxi Driver, while in the women’s bathroom there is a mural of the title character from Stanley Kubrick’s Lolita. During two separate scenes in the film, posters of Iggy Pop are visible in the background of both of Tommy’s apartments. Aside from direct narrative and visual references, the film’s soundtrack consists almost entirely of American and British bands, including Iggy Pop, Lou Reed, Blondie, Underworld, and New Order.

Much of the dialogue and imagery concerning American musicians subversively criticizes the overwhelming influence of American pop culture in Scotland, but American artists dominate the soundtrack, reflecting the very influence that is being criticized. During one scene set in a park, Mark and Sick Boy discuss the inevitable decline of American artists such as Elvis Presley, Lou Reed, and even Iggy Pop. Later in the film, Diane mistakenly claims that “Iggy Pop is dead.” By portraying American artists as failures, the film is taking a jab at its own cultural influences. Strategically placed posters of Iggy Pop continue this criticism of American influence. In the scene where Tommy and Lizzy discover they are missing a tape of themselves having sex, a fight ensues that eventually leads to Tommy becoming a heroin addict. A large poster of Iggy Pop is visible in the background throughout this scene. Later, after Tommy has developed HIV, Mark comes to visit him in is dingy, depressing apartment, where the only decoration is a poster of Iggy Pop on the wall. By associating an American artist with the downfall and death of Tommy, arguably the most likable and most stereotypically “Scottish” character, the film is indirectly blaming the intrusion of American pop culture for the downfall and “death” of Scottish national identity.

Trainspotting Analysis: A Frenetic Visual Style

Though much of the narrative resembles that of the classical Hollywood cinema, the visual style is also heavily influenced by American cinema and pop culture. In particular, the editing and camera movement resemble the look of a Hollywood action movie. These visual styles are not only a testament to the influence of American cinematic style on Scottish filmmaking, but also an attempt by Boyle to use “industrially aspirant adaptation of US cinematic precedents and working practices, in a bid to construct a commercially viable Scottish feature” (Murray 217). The use of fast-paced music and quick editing together is also a result of the rise of the music video in the United States.

In Trainspotting, a breakneck pace is set from the very first scene. Having been caught for shoplifting, Mark and Spud run down a busy street with security guards in hot pursuit. Iggy Pop’s up-beat song “Lust for Life” is playing while Mark narrates the scene. However, it is more than just the music and the action on screen that set the pace; it is also the movement of the camera and the fast-paced editing. Though the location quickly shifts to another space where Mark is shooting up, the opening scene on the street lasts just under 30 seconds and uses 13 different shots. The camera is almost constantly moving to capture all the kinetic energy on screen, giving this brief moment a greater sense of urgency.

The narration continues over several different places, including a soccer field where the gang is playing and a beat up apartment where they cook heroin. All the while, the music continues so as not to lose the pace established in the first 30 seconds. A similar approach is used when the three respective couples in the film (Tommy and Lizzy, Spud and Gail, Mark and Diane) return home after a night at the dance club. While at the club, Blondie’s song “Atomic” begins to play when Mark first sees Diane, and the song continues as all three couples depart for their respective sexual encounters. From the moment they leave the club, the entire scene lasts about 2 minutes and 30 seconds, and consists of 42 shots, with each subsequent shot getting shorter as the scene progresses.

The quick editing adds to the sexual energy and comedy of the scene. Mark is the only one who is successful in his encounter, while Tommy falls short due to a mix up with a pornographic videotape, and Spud passes out from drinking. Both of these scenes resemble the fast-paced energy of American action films, while also utilizing the fast editing and poppy music of early 90’s music videos.

Trainspotting Analysis: Scottish Post-Modernism

Trainspotting is interesting in its ability to be strangely self-aware. The film is heavily influenced by different social and artistic influences, and yet it is able to make social commentary and even directly reference many of its own influences. This odd self-criticism by Boyle seems like yet another example of the Scottish confusion over identity: while the film seeks to criticize the forces influencing its aesthetics, it nevertheless gives in to those influences. The visual style is similar to many American films, while much of the different narrative qualities can also be attributed to classical Hollywood cinema and American pop culture.

The social aspects of the film reflect the dominance of England and the impact of colonialism, which in tandem with American pop culture and Thatcherism caused a lack of national identity in Scotland that is reflected in the narrative of the film. While Trainspotting is definitely a unique film, it is hard to define where its origins lie. It was made in Scotland by an English director, with a mostly Scottish cast, using Scottish dialect, and yet it is somehow not Scottish. But is it even possible for a film to be Scottish? With the years of economic and social oppression from England and the social takeover by American pop culture, it is hard to say that Scotland has any kind of distinct culture to be shown in film.

Cardullo, Bert. “Fiction into Film, or Bringing Welsh to a Boyle.” Literature Film Quarterly 25.3 (1997): 158-62.

Elsaesser, Thomas. European Cinema: Face to Face with Hollywood. Amsterdam: Amsterdam UP, 2005.

Gardiner, Michael. From Trocchi to Trainspotting: Scottish Critical Theory since 1960. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2006.

Murray, Jonathan. “Kids in America? Narratives of Translatlantic Influence in 1990s Scottish Cinema.” Dossier 46.2 (2005): 217-25.

Smith, Murray. Trainspotting. London: British Film Institute, 2002. Stollery, Martin. Trainspotting. London: York, 2001.

Thomsen, Robert. “The Development of Scottish Nationalism.” (1997). 05 Dec. 2011. Web. <earth.subetha.dk/~eek/museum/auc/marvin/www/library/uni/projects/scotsnat.htm>

Your notes should have been included as a “Bonus Feature” in the criterion (or any other) release of this film. Trainspotting is not a film I’ve yet seen, but I will bookmark this post to have as a reference when I do see it.

Thank you for providing such thoughtful context for this film – and for this era. And thanks for sharing all your research with us. 🙂

Your notes should have been included as a “Bonus Feature” in the criterion (or any other) release of this film. Trainspotting is not a film I’ve yet seen, but I will bookmark this post to have as a reference when I do see it.

Thank you for providing such thoughtful context for this film – and for this era. And thanks for sharing all your research with us. 🙂

What a load of pish.

Love,

Scotland