<p><em>The Piano Teacher</em> (2001) is a film directed by Michael Haneke, based on the 1983 novel of the same name by Elfriede Jelinek. It tells the story of Erika Kohut (Isabelle Huppert), a piano teacher at a prestigious music conservatory in Vienna, who becomes involved in a sadomasochistic relationship with her student, Walter (Benoît Magimel). Despite moments of extreme violence and graphic sex, <em>The Piano Teacher</em> is a complex and multi-layered exploration of isolation, repression, and desire. Haneke makes extensive use of space to convey Erika’s unpredictable state of mind, as well as the dynamics of her troubled relationships.</p>

<p>The film opens with Erika returning to a dark, claustrophobic apartment, where her mother (Annie Girardot) waits for her. The mother scolds Erika for arriving late, and their argument quickly turns to violence. Eventually, they succumb to tears and hold one another. Later in the evening, the mother and daughter sleep in the same bed. Their relationship remains strained and antagonistic throughout the rest of the film. ;</p>

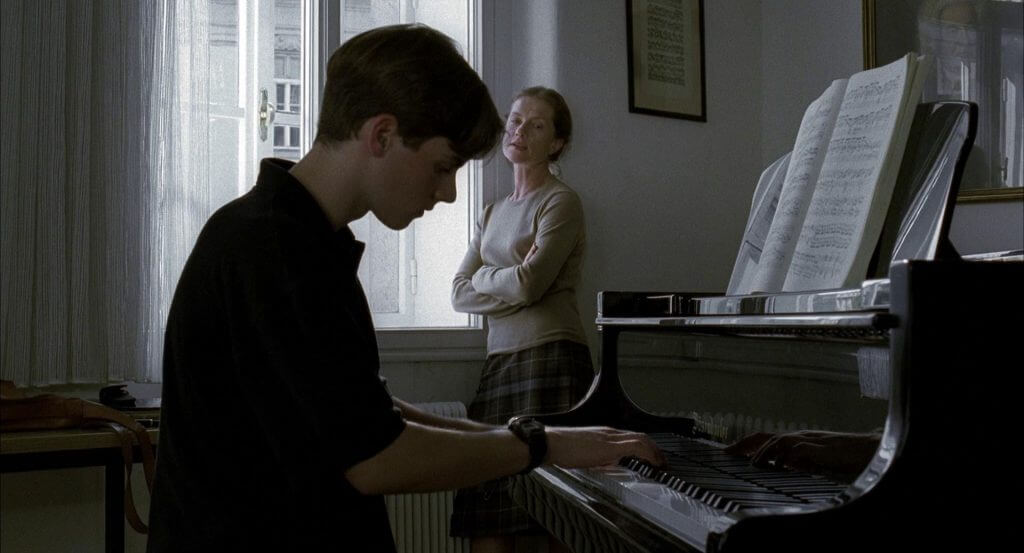

<p>Early on, Haneke establishes the apartment as a cold place in which Erika and her mother live completely cut off from everything and everyone. When Erika does venture out into the world to teach private piano lessons, she is often at the center of the frame, standing in the background and looking down on her pupils. ;</p>

<p>She chastises her students for relatively minor mistakes. The room where Erika conducts her classes is well-lit, and the juxtaposition between the apartment and the private classroom is jarring. In the dimly lit apartment, Erika is constantly under attack and powerless against her overbearing mother. Alternatively, in the bright classroom, Erika can exercise her power as a respected pianist over her young, submissive students. ;</p>

<p>Later, Erika performs a home recital for her peers and fellow enthusiasts. Though her performance is well-received, she remains aloof and isolated from the people. When Walter shows an unusual interest in her work, Erika dismisses him coldly. Throughout the evening, people can be seen happily bustling around, eating, drinking, and socializing. In contrast, Erika remains separated from the people, often by herself, with her mother, or reluctantly cornered by Walter. ;</p>

<figure class="wp-block-image aligncenter size-large"><img src="https://philosophyinfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/3417b8a748cf97eb65680be9241b4523-1024x576.jpg" alt="The Piano Teacher cinematography" class="wp-image-2640"/><figcaption class="wp-element-caption">Erika stands alone in her private classroom (<em>The Piano Teacher</em>, 2001)</figcaption></figure>

<p>Haneke uses similar framing of Erika when she’s moving through the city. For example, when she walks to a nearby sex shop, she is positioned at the forefront, with the public moving about behind her. A man runs into her, suddenly thrusting her into the same space as everyone else, which bothers Erika immensely. Still, she continues to her destination, with virtually no interaction with the world around her. As she watches a pornographic film in an isolated booth, she shows a sense of calm that she cannot attain out in the world, or even in the “comfort” of the apartment she shares with her mother.</p>

<p>When Walter auditions for Erika and her colleagues, Erika is positioned on the left side of the frame, far removed from everyone in the room. As she discusses Walter’s fate with her colleagues, the camera shifts between a static closeup of Erika’s face and a wider shot of the other professors. They are represented collectively, while she remains alone. ;</p>

<p>Soon after, Erika goes to a busy cafeteria, full of young students talking and eating. She sits alone against the far wall, watching the people in silence. Her status as a perpetual outsider is only further reinforced when she visits a local drive-in theater on foot. After finding a young couple having sex in their car, she squats nearby and urinates, only to be chased away when she is discovered.</p>

<p>After watching Walter flirt with one of her female students, Erika uses her isolation to seek revenge. Since no one seems to notice her, she slips through a side door during a rehearsal and fills the girl’s jacket pocket with broken glass. She then calmly takes a seat back in the auditorium, once again physically separating herself from the rest of the onlookers. ;</p>

<figure class="wp-block-image aligncenter size-large"><img src="https://philosophyinfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/screenshot-265-1024x546.png" alt="The Piano Teacher analysis" class="wp-image-2641"/><figcaption class="wp-element-caption">Erika looks for her student&#8217;s jacket to exact revenge (<em>The Piano Teacher</em>, 2001)</figcaption></figure>

<p>As the film progresses, Haneke begins to use space in more complex and nuanced ways. In the scene in which Erika and Walter have their first sexual encounter in a public bathroom, Haneke uses space to dissect the world of Erika’s fantasies from the world of her professional life. The only thing that separates her extreme transgression from her livelihood is a bathroom door, but she doesn’t seem to care. Later, when Walter attempts to have sex with Erika in her practice room, she resists. Not only does Erika oppose Walter making any decisions in their relationship, but she also does not appreciate the intrusion into the only space where she always has power. ;</p>

<p>After giving Walter a list of commands for their relationship, they reconvene at her apartment. Erika’s mother protests, but Erika ignores her and retreats to an unused bedroom. Walter and Erika barricade themselves inside the room to keep her mother out, but once Walter realizes the extremity of Erika’s sadomasochistic desires, he leaves. ;</p>

<p>Erika, now obsessed with making the relationship work, pursues Walter to an ice rink where he is playing hockey. The two attempt to have a private conversation, just feet away from his teammates. This quickly turns into a bizarre sexual encounter gone wrong. Walter is disgusted by Erika, and she flings open the doors and runs out of the ice to escape the embarrassment. </p>

<figure class="wp-block-image aligncenter size-large"><img src="https://philosophyinfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/tumblr_bf964dacc24f8edb0adbd368d1104b9c_5c2de269_1280-1024x550.png" alt="Isabelle Huppert movies" class="wp-image-2647"/><figcaption class="wp-element-caption">Walter shows disgust with Erika after an awkward sexual encounter (<em>The Piano Teacher</em>, 2001)</figcaption></figure>

<p>Their mutual sexual frustration reaches a climax soon after, when Walter barges his way into the apartment to berate Erika. He locks her mother in the bedroom and begins beating Erika, purportedly giving in to the “commands” from her list. Erika weakly tries to fight him off. In this scene, Erika is huddled on the ground, her nose bleeding, while Walter stands over her. He then gets on top of Erika and rapes her.</p>

<p>In the film’s final sequence, Erika attends a recital with her mother. She is meant to be the main performer, but she appears distracted. As people rush past her to get into the auditorium, she looks around the lobby for Walter. Some people greet her, seemingly unaware of her black eye and disheveled appearance. Walter greets her from a distance and moves quickly into the auditorium, robbing Erika of her chance at revenge. It is at this moment that Erika stabs herself in the shoulder and walks out. ;</p>

<p>Haneke refuses to pass judgment on his characters, allowing the audience to come to their own conclusions about the morality of their actions. Erika is a complex and contradictory figure, at once a victim and a victimizer. She is a woman who has been repressed for so long that she has become desperate for any kind of release, even if it means inflicting pain on others. She is either trapped in a cramped, cluttered apartment, or she is emotionally and sexually confined in a world that simultaneously puts her on a pedestal and ignores her very existence. Meanwhile, the mother is both lonesome and loathsome, torturing her daughter with incessant ridicule. Lastly, Walter begins as a brash young artist seeking attention, but devolves into a violent rapist, seemingly confused by what he actually wants and what Erika wants from him. ;</p>

<p>Haneke emphasizes Erika’s isolation by using tight, claustrophobic framing and camera angles that convey a sense of entrapment. Her isolation is particularly evident in the scenes in which Erika practices piano. These are shot in extreme close-ups, emphasizing her physical and emotional intensity, while also physically cutting her from the rest of the world.</p>

<p>The use of space is also notable in the relationship between Erika and Walter. Haneke often frames the pair in two-shot compositions to reflect the emotional distance between them. This distance is reinforced by the fact that they often occupy different spaces within the frame, with Erika typically in the foreground and Walter in the background. It is symbolic of the unbalanced power dynamic, in which Erika and Walter exert varying degrees of control over one another.</p>

<figure class="wp-block-image aligncenter size-large"><img src="https://philosophyinfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/image-w1280-1024x576.webp" alt="The Piano teacher rape" class="wp-image-2642"/><figcaption class="wp-element-caption">Erika looks for Walter in the lobby as guests enter the auditorium (<em>The Piano Teacher</em>, 2001)</figcaption></figure>

<p><em>The Piano Teacher</em> is a film built on the contrast between public and private spheres. Erika&#8217;s home is a private space that her mother keeps tightly controlled, while the conservatory is a public space in which she is forced to interact with others. The tension arises from Erika’s desire to live out repressed fantasies without sacrificing her public image. She is desperate for human connection, but physically and emotionally retreats from human contact as often as possible. ;</p>

<p>Michael Haneke uses space and isolation in <em>The Piano Teacher</em> to convey the emotional and psychological state of his protagonist, and to explore the complex dynamics of her relationships with her mother, Walter, her students, and the world at large. Through his use of insulated framing, tight camera angles, and contrasting settings, Haneke creates a visual showcase of isolation and repression.</p>

<p>If you&#8217;d like to watch <em>The Piano Teacher</em> (2001), the film is currently available to <a href="https://amzn.to/42onW4n" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">buy, rent, or stream on Amazon</a> or <a href="https://play.hbomax.com/player/urn:hbo:feature:GYSVAtQdRMMImwwEAAAA5" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener">HBO Max</a>. For more film essays like this one, be sure to check out the <a href="https://philosophyinfilm.com/">Philosophy in Film homepage</a>!</p>

Space and Isolation in Michael Haneke’s The Piano Teacher