<p>In the years following the 1948 Paramount Case, independent cinema gained a competitive edge in the United States. As the importation of more lurid European films increased, the Production Code loosened its requirements restricting violence and overt sexuality. These changes paved the way for the rise of the “sexploitation” genre of the 1960’s. Films of this genre were produced on small budgets, but exploited erotic narratives and nudity to attract (heterosexual male) audiences. One director who specialized in this genre was Radley Metzger. However, while Radley Metzger exploited sexual themes to attract male audiences, his films created a hybrid of art cinema and sexploitation by emphasizing more progressive concepts of gender and sexuality through the narrative representations of women and the visual abstraction of the female body.</p>

<p>Before becoming a director of feature films, Radley Metzger helped edit and distribute European art films for US exhibition. His distribution company, Audubon, even distributed the highly controversial and influential film <em>I, A Woman </em>(1965) to US markets. As Radley Metzger transitioned from distribution to production, his style reflected American interest in the European art cinema. The cinematographic approach and sexual themes that Metzger implemented helped his small-budget films attract an audience that was becoming increasingly interested in film art and sexuality. Since heterosexual men comprised the majority of the target audience, films of the sexploitation genre put particular emphasis on the female body. This emphasis, and the genre’s appeal to male voyeurism, put the new genre in direct opposition to the second wave of feminism in the late 1960’s.</p>

<p>The rise of second wave feminism, combined with the social and industrial context of the 1960’s American film industry, put Radley Metzger at a crossroads. The industry essentially required small-budget films to have sensational content in order to turn a profit. However, this era was also characterized by drastic social change and a reevaluation of gender roles in the US. As a result, Radley Metzger innovated a hybrid genre by combining the “high culture status of the foreign art film and the rough-hewn, low-cult material of the sexploitation feature” (Gorfinkel 27).</p>

<p><strong>» You Might Like:</strong> <a href="https://philosophyinfilm.com/2017/04/04/review-ghost-in-the-shell-2017/">Review: <em>Ghost in the Shell</em> (2017)</a></p>

<p>While the overtly sexual content of Radley Metzger’s films drew in audiences, it was the progressive themes and European art film aesthetic that elevated them above the level of mere “nudie pictures.” These themes were especially prevalent in three of Radley Metzger’s most notable sexploitation films: <em>The Alley Cats</em> (1966), <em>Therese and Isabelle</em> (1968), and <em>The Lickerish Quartet </em>(1970). Though these films differ in their graphic representations of nudity, Metzger continually chose to imply sexuality and separate the act of sex from the female body by attracting attention to the sensuality of the films themselves. Radley Metzger also created narratives that centered on the plights of women trapped in patriarchal societies and portrayed them as victims of a larger social wrong.</p>

<p>For example, the female characters in <em>The Alley Cats </em>are portrayed as women who want to be free from the sexual constraints that men, and society as a whole, have imposed on them. These representations are in direct opposition to the depictions of women in most mainstream films of the 1960’s and 1970’s. Feminist film critic Molly Haskell writes that, compared to the female stars of early Hollywood, female stars of the 1960’s and 1970’s are portrayed as “whores, jilted mistresses, emotional cripples, and drunks” who are “less intelligent, less sensual, less humorous, and altogether less extraordinary” (Haskell 329). In the films of other sexploitation directors, such as Russ Meyer, women are either portrayed as dim-witted vixens or violent and sexualized she-devils who get what is coming to them. In one of Meyer’s most notable sexploitation films, <em>Faster Pussycat! Kill! Kill!</em> (1965), the central female character, Varla, is an ultra-violent, man-hating sadist, whose exploits can only be stopped with her death at the end of the film. Alternatively, a bikini-clad teenage girl that Varla kidnaps is portrayed as unintelligent, helpless, and completely reliant on men for her salvation.</p>

<figure class="wp-block-image aligncenter size-full is-resized wp-image-575"><img src="https://philosophyinfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/288c1d9c5653d03d787657bd31fa86dd.jpg" alt="Radley Metzger Faster Pussycat Kill Kill" class="wp-image-575" style="width:800px;height:600px"/><figcaption class="wp-element-caption">21Varla acting out her hatred for men in <em>Faster Pussycat! Kill! Kill!</em> (Radley Metzger, 1965)</figcaption></figure>

<p>However, the women of Metzger’s films do not fit into these negative representations. Instead of the narratives characterizing women as “whores,” Radley Metzger’s films most often portray them as sexually liberated women in sexually repressive societies. For example, the protagonist in <em>The Alley Cats</em>, Leslie, is trapped in an unhappy marriage with Logan. It is clear that Leslie is unhappy, and even confused about her sexuality, but this goes unnoticed by her husband. Meanwhile, Logan begins an affair behind Leslie’s back. In turn, Leslie meets a charming man with whom she has a one-night stand, only to find the bed empty the next morning. As Leslie’s unhappiness reaches a breaking point and she considers suicide, an attractive and mysterious woman, Irena, takes her in. The two have a brief sexual encounter, only to be interrupted by Logan, who is enraged to discover that his wife would cheat on him, especially with another woman.</p>

<p>Logan’s disgust with Leslie’s affair (despite his own infidelity) is one example of the hypocrisy regarding sexual promiscuity between men and women, and emblematic of the struggle of feminists to gain the right to “extramarital sexual relations free from the atrocious label of ‘adultery’” (<em>Radical </em>52). <em>The Radical Women Manifesto: Socialist Feminist Theory, Program and Organizational Structure</em>, published in 1973, traces the origins and history of the subordination of women and supplies a list of demands to overcome patriarchal control. It puts particular emphasis on the negative representations of women in media, and the institution of US capitalism as one that “degrades and dehumanizes women by the stereotypes it fosters, but proceeds to profit from the stereotypes themselves…[I]t is also stock in trade to exploit women’s bodies to sell everything from toothpaste to computers” (<em>Radical</em> 33). These institutions of patriarchal control form the central conflict in <em>The Alley Cats</em>, as Leslie feels trapped by the role society has chosen for her and her husband’s attempts to control her sexuality.</p>

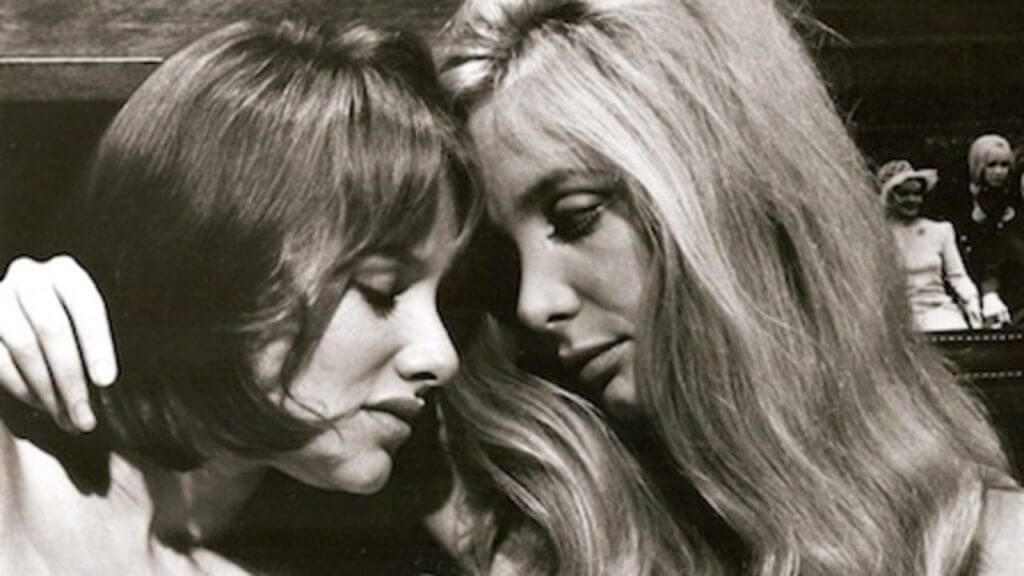

<figure class="wp-block-image aligncenter size-full is-resized wp-image-576"><img src="https://philosophyinfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/The-Alley-Cats-04.jpg" alt="Radley Metzger The Alley Cats" class="wp-image-576" style="width:800px;height:340px"/><figcaption class="wp-element-caption">Leslie and Irena share a meaningful glance (<em>The Alley Cats</em>, Radley Metzger, 1966)</figcaption></figure>

<p>The film ends with Logan attacking both Irena and Leslie, only to have Leslie gratefully return to him as the credits roll. While the story arc seems to promote a more conventional, patriarchal reflection on relationships and sexuality (woman is unhappy with man, woman explores her sexuality, man beats woman, woman learns her lesson and returns to man), a closer analysis of the representations of gender and power relations in the narrative reveals subversive themes.</p>

<p><strong>» You Might Like:</strong> <a href="https://philosophyinfilm.com/2017/02/15/sex-and-the-creation-of-horror-in-it-follows/">Sex and the Creation of Horror in <em>It Follows</em></a></p>

<p>The men and women portrayed in the film (both central and peripheral characters) serve varying, non-conventional roles in the narrative. Leslie is portrayed as a sympathetic character, with her anguish stemming from the tension between oppressive conventions of society and her own sexual desires. The society of the 1960’s imposes conflicting regulations on women: women must be sexually appealing to men, but they also must not flaunt or explore their sexuality. In such a society, women are seen as the “property of men,” with little control over their “minds and bodies” (<em>Radical </em>51). This conflict becomes apparent early in the film when Logan asks Leslie, “Honey, how many times have I told you to wear pants?” only to complain later that Leslie has no sex appeal. Logan wants to have complete control over Leslie, attempting to make her both sexual and asexual. In this respect, he represents the oppressive society and the quintessential male of Radley Metzger’s films. Logan is unintelligent, violent, and an overbearing force in Leslie’s life. Until the final moments of the film, when Leslie gratefully returns to Logan, he is portrayed as the antagonist and a barrier to Leslie’s happiness. The ending, which contradicts the themes established in the first 80 minutes of the film, seems to be tacked on to compensate for the arguably emasculating storyline, and to give male audiences a sense of sexual satisfaction. Since the narrative does not elicit any male-identification with Leslie, the ending allows for the male spectator to identify with Logan and provides a satisfying conclusion.</p>

<figure class="wp-block-image aligncenter size-full is-resized wp-image-581"><img src="https://philosophyinfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/0018c1eb.png" alt="The Alley Cats" class="wp-image-581" style="width:800px;height:325px"/><figcaption class="wp-element-caption">Leslie and Irena have a brief moment of passion before Logan discovers them (<em>The Alley Cats</em>, Radley Metzger, 1966)</figcaption></figure>

<p>The character of Irena represents the ideal woman in the film: sexually liberated and free of men. She also serves as a counterbalance to Leslie’s character through her “rejection of the passive ‘feminine’ role” (<em>Radical </em>63). Early in the film, Leslie and Logan attend a party and meet Irena for the first time. During the party, Irena retreats to a backroom where she has a young, anxious man waiting for her. As she enters the room, she sees that he has brought a whip with him. She takes the whip from him, while an anonymous female partygoer enters the room. Irena begins whipping the man off-screen as the third female smiles. This scene shows the female character, Irena, as one who is capable of being dominant over the male character (who becomes the passive “victim” of sexual aggression), while also allowing for the implied objectification of the male body through the gaze of the anonymous female voyeur.</p>

<p>Later, after Logan attacks Leslie and Irena for sleeping together, he pursues Irena out to the street. As he comes toward her, she turns and begins to mock him, “go ahead, you’re strong enough for me but you’re not man enough for her.” Logan immediately stops and looks humiliated. She implies that even though he is strong enough to beat up women, he is not able to please his wife sexually. Thus, while Leslie represents the female that is a victim of patriarchal society, Irena represents the female who resists convention and is dominant over men.</p>

<p><strong>» You Might Like:</strong> <a href="https://philosophyinfilm.com/2016/03/06/gender-and-female-sexuality-in-breillats-fat-girl/">Gender and Sexuality in Breillat&#8217;s <em>Fat Girl</em></a></p>

<p>Similar to <em>The Alley Cats</em>, <em>Therese and Isabelle</em> is critical of the society that imposes oppressive gender roles on women. In the film, the narrative unfolds as a series of flashbacks. As an adult, Therese visits the all-girls school that she attended as a teenager, recalling memories of her time there. During her first days at the school, Therese meets a young man from another school who tries to seduce her. When his attempts fail, he rapes her. While Therese tries to deal with this trauma, she meets Isabelle. The two girls quickly fall in love and find themselves in an affair that they must keep from the puritanical school authorities and their overbearing parents. However, due to forces beyond their control, namely the “intolerance” of society, Therese and Isabelle are eventually torn apart, never to see each other again (Mellen 74).</p>

<figure class="wp-block-image aligncenter size-full is-resized wp-image-577"><img src="https://philosophyinfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/thereseandisabellovers.png" alt="Therese and Isabelle" class="wp-image-577" style="width:800px;height:380px"/><figcaption class="wp-element-caption">A rare instance of nudity as Therese and Isabelle contemplate the future of their relationship (<em>Therese and Isabelle</em>, Radley Metzger, 1968).</figcaption></figure>

<p>The narrative itself emphasizes the distinction between the two girls (as prisoners) and the rest of society (as the prison). Radley Metzger is careful not to trivialize their plight, deciding instead to portray them as “strong young women whose relationship resonates with transgressive power” (Morris). The narrative is seen through the eyes of Therese, encouraging the audience to sympathize with her struggle. She is portrayed as a victim, with her greatest antagonists being rape, sexual repression, and homophobia. The use of a female protagonist opposes the general trend of the 1960’s, a period in which the focus is “generally on the male protagonist, often the director’s alter ego…That a woman might not be entirely satisfied with her lot in life, or might want to let go with a little insanity of her own, never occurs to these protagonists, or to their creators” (Haskell 335). In <em>Therese and Isabelle</em>, Therese is the hero. She is the alienated spirit who must cope with a male society that exercises its power on her mind, through forced gender roles, and body, through rape.</p>

<p>Though the film still portrays nude female bodies (albeit sparingly), the narrative focuses on the plight of both Therese and Isabelle to be together despite the overwhelming odds. Thus, the spectator is made to see the psychological strain that a patriarchal society can put on women, while the film deemphasizes the women’s bodies as objects of visual pleasure. During a scene in which both girls discuss their situation on the way to class, Isabelle states that “we can’t run away. This is where we have to be.” Later, they flee to a nearby hotel that also serves as a brothel to have a moment alone with each other. When the girls enter the lobby they see dozens of birds locked in cages. Both of these narrative elements refer back to the sense of helplessness that the girls experience. Therese and Isabelle realize that they have to be there, as they are metaphorically locked in a cage. They must serve certain male-defined roles in a society that they cannot escape.</p>

<p>The film also illuminates subtle ways in which patriarchal societies have an oppressive hold over women’s bodies. During a scene portraying intercourse between Therese and Isabelle, the narrator (adult Therese) refers to the clitoris as the “pearl,” which was the “little male organ all of us had.” Even with her own body, Therese cannot identify her sexual organs in gender-specific ways. Rather than being a uniquely female organ, it is simply a smaller version of a male organ. In an oppressive, male-dominated society, female identity and sexuality can only be defined in relation to masculine terms.</p>

<p>Though <em>The Lickerish Quartet</em> has the most nudity of all three films and focuses less on the negative effects of a patriarchal society, the narrative does make a self-reflexive attempt to condemn the “low-brow” spectator of the sexploitation film. The film embodies the duality of Metzger’s “hybrid” genre, which makes a “claim for the ‘average’ audience and purportedly deflects the more ‘prurient’ viewer who is out to see flesh regardless of the finer points of story, sentiment, and ambience” (Gorfinkel 30). <em>The Lickerish Quartet</em> begins with the image of a black and white soft-core pornographic film, or “stag” film, accompanied by the sounds of a man breathing heavily and giggling off screen. The shot changes to reveal that this character is a man projecting the film in his home, accompanied by his wife and son. After discussing the film, the family goes to a carnival where they see a woman who looks exactly like one of the actresses in the film. The father convinces her to come back to their mansion. As the night continues, the woman has sexual encounters with all three family members. With each subsequent encounter, it becomes harder to distinguish between what is “real” and what is fictional. The characters become the actors in the stag film, switching in and out of the roles. By the end of the narrative, the people who were originally in the stag film now sit in the living room, watching the film with the father, wife, and son occupying the images on screen.</p>

<p>By showing the act of watching a stag film, during which the male voyeur pants and ogles the naked women, the opening scene draws the spectator’s attention to his own participation in the film. As feminist theorist Laura Mulvey puts it, the male voyeur finds pleasure through “scopophilia” in which “looking itself is a source of pleasure” (713). The spectator looks at the women on screen “as objects, subjecting them to a controlling and curious gaze” (Mulvey 713). By showing the spectator an image of a man finding pleasure through scopophilia, the film holds up a mirror to male spectators that desire to be “entertained and aroused” rather than “educated and edified” (Gorfinkel 30).</p>

<p>During the viewing of the stag film, the family enters into a discussion about the actors and actresses having sex on screen. The wife wonders aloud if “they’re enjoying it, or just faking…it must be distracting knowing people are watching. Knowing people are going to watch.” While the sex of the stag film is more explicit than what is usually portrayed in Radley Metzger’s films, it still directly addresses the problem that his films serve as objects for sexual voyeurism. The son, incredulous that his parents are enjoying the film, states that he “doesn’t know what [they] get out of all this.” The film simultaneously provides sexual gratification for the spectator and condemns the act of watching for the sake of sexual gratification. The son continues this condemnation: “It must be a comfort to know that you can control things with nothing more than the quick flip of a switch.” This reflects the “controlling gaze” that creates an uneven power dynamic between the male spectator and the woman being viewed on screen (Mulvey 713). Due to the nature of film as a medium, the male viewers (indeed, Metzger himself) suddenly have power over the female that is objectified. This fact is exemplified when the father watches the film again in reverse, and a third time in high-speed. Later in the film, this “need” to have control over women is explained through the father’s anxieties about his own impotence. He combats his insecurities through film, which allows him to be both voyeur and puppet master to the women on screen.</p>

<p>The switching between narrative “reality” and the “fiction” of the stag film breaks down the barrier between spectator and film. While a spectator of Metzger’s films can enjoy the nudity and sexuality as a voyeur, it suddenly becomes problematic when the film proposes that the actors on screen are actual people, and that the spectator could just as easily be in the film as in the theater. By shortening the distance between spectator and film narrative, it becomes harder for the male audience to objectify the women on screen.</p>

<p>While it has already been established that the narrative themes of Radley Metzger’s films reflect progressive representations of women, it is Metzger’s visual abstraction of sex that allows for his films to be sexploitation without putting emphasis on the female body. Instead, they focus on “the refined art of the tease.” (Gorfinkel 34). This is most evident when compared to the films of fellow sexploitation director, Doris Wishman. In her 1973 film <em>Love Toy</em>, a down-on-his-luck father gambles away his daughter’s body to another man. The narrative focuses on the degrading sexual acts that the man forces the teenage girl to participate in. In one such scene, the man makes her take off her clothes and lick milk out of a bowl like an animal, while the camera lingers on her naked body and keeps the image at the center of the frame. In this way, the film, rather than criticizing the subjugation of women in patriarchal society, capitalizes on the “violent and inhumane exploitation of women to maintain dominance” (<em>Radical</em> 69). While the nudity and highly graphic depictions of sex can be partially attributed to the shift from sexploitation to hardcore pornography in the mid-70’s, they are also a reflection of Wishman’s style and adherence to patriarchal norms in film (Schaefer 5). Even in her earlier works, such as <em>Blaze Starr Goes Nudist</em> (1962) and <em>Bad Girls Go to Hell</em> (1965), Wishman uses the display of the female body and perverse sexual power relations to attract heterosexual male audiences. While these visual and narrative elements form the basis of the sexploitation genre, Radley Metzger reworks the genre to shift the focus away from the female body.</p>

<figure class="wp-block-image aligncenter size-full is-resized wp-image-580"><img src="https://philosophyinfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/badgirls2.jpeg" alt="Radley Metzger Bad Girls Go to Hell" class="wp-image-580" style="width:800px;height:580px"/><figcaption class="wp-element-caption">The female body is on full display in Wishman&#8217;s <em>Bad Girls Go to Hell</em> (1965).</figcaption></figure>

<p>This practice of visual abstraction is an important point in regards to feminist theories of the late 1960’s, in which feminists place the “sexual objectification” of the “female body at the center of their earliest manifestos” (Evans 344). It is this use of the female body that forms the foundation of the sexploitation genre. In spite of this, Metzger does not focus on the female form in his films. In scenes depicting intercourse, the mise-en scene is used as a substitute for the female body. Radley Metzger uses “decorative objects such as sculptures, glass bottles, furniture and mirrors, and creative attention to off-screen space” to imply sex and titillate the audience without relying on the female form (Gorfinkel 34). For example, in <em>The Alley Cats</em>, Leslie’s first sexual encounter is implied mostly through point of view shots from her perspective. As she receives oral sex, we catch glimpses of different parts of the room and ceiling, occasionally seeing Leslie’s head as a reflection in a mirror. As Leslie nears climax, the shots are edited together more rapidly and the room begins to spin, ending with a close-up of Leslie’s face. In Radley Metzger’s films, “it is the <em>style itself</em> that is being eroticized,” rather than the female body (Gorfinkel 35).</p>

<p>A later sex scene between Logan and his mistress, Agnes, is seen through distorted and disorienting imagery. The image of both bodies is blurry to the point of being unidentifiable. In this scene, the “images arrest the motion towards representational truthfulness of the sexed body in favor of presenting sex as aesthetically mediated or dematerializing” (Gorfinkel 34). By either distorting the image of the body or bypassing the image entirely, Radley Metzger directs the spectator to the sensuality of his own style, rather than the desirability of the female body.</p>

<p><strong>» You Might Like:</strong> <a href="https://philosophyinfilm.com/2014/05/10/responsibility-and-victimization-in-grave-of-the-fireflies/">Responsibility and Victimization in Grave of the Fireflies</a></p>

<p>Similarly to <em>The Alley Cats</em>, the sex scenes in <em>Therese and Isabelle</em> are always portrayed through suggestive mis-en-scene or descriptive narration. When Therese and Isabelle kiss for the first time, they are only visible as shadows behind a curtain. Later, when their relationship becomes more physical, the narrator describes the events taking place while the camera pans away. In Richard Corliss’ review of the film, even the rape scene is described as “tame,” with both characters being “fully clothed” (Corliss 64). Although the girls’ breasts are shown at certain moments throughout the film, the nudity is scarce and is most often distorted. The last time that the girls sleep together is only shown as a shaky reflection in the water of a nearby creek.</p>

<figure class="wp-block-image aligncenter size-full is-resized wp-image-579"><img src="https://philosophyinfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/409f9757e52f647382278790a60369c5.jpg-1.png" alt="Radley Metzger The Lickerish Quartet" class="wp-image-579" style="width:800px;height:400px"/><figcaption class="wp-element-caption">The library scene in <em>The Lickerish Quartet</em> (Radley Metzger, 1970)</figcaption></figure>

<p>While the sex scenes in <em>The Lickerish Quartet</em> are the most explicit of all three films, the camera never lingers on the female body. When the mysterious woman from the stag film seduces the father in the library, she is only seen naked for a moment. When they begin to have sex, the camera focuses on the stylized set that the characters occupy. The library floor has thousands of words written on it referring to sex and genitalia. The camera pans to different words as we hear the two characters having sex in the background. Later, when the woman and the son have sex, it is seen through extreme long-shots, in which the characters only appear as tiny figures, or extreme close-ups, in which both the male and female face occupy the entire screen. Similarly, the stag film that is shown throughout the narrative uses extreme close-ups of the actors’ faces. The film uses the promise of sexuality to attract audiences, but the display of the female body is always minimal and “discreet” (Schaefer 5).</p>

<p>While it cannot be ignored that the sexual themes of Radley Metzger’s films are used to attract and titillate heterosexual male audiences, his representations of women and frequent abstraction of the female body reflect deference for the feminist ideals of the 60’s and 70’s. Metzger uses male characters to represent the misogynistic American society, while the female characters represent the heroes of the narrative, who try to find sexual liberation and freedom from oppression (both successfully and unsuccessfully). The use of clever mise-en-scene allows visual style to be the source of pleasure for the spectator, rather than the image of the nude female. In doing this, the films dismiss the “low-brow” sex film audience in favor of spectators seeking a combination of art and erotica. In the light of the feminist movement of the 1960’s and the changing conceptions of gender and sexuality, Radley Metzger’s films exceed the classification of being mere sexploitation.</p>

<p><strong>*Originally Published in Film Matters Magazine (Issue 4.4): ;<a href="https://www.intellectbooks.com/film-matters"></a><a href="https://www.intellectbooks.com/film-matters">https://www.intellectbooks.com/film-matters</a></strong></p>

<p><strong>*Jones, Matthew. &#8220;Metzger&#8217;s Women: Gender Representations and Visual Abstraction in &#8217;60s Sexploitation.&#8221; ;<i>Film Matters</i> ;Dec. 2013: 12-18. Print.</strong></p>

<p><strong>Corliss, Richard. &#8220;Therese and Isabelle.&#8221; Rev. of <em>Therese and Isabelle</em>. <em>Film Quarterly</em> 22.1 ;</strong><strong>(1968): 63-67. Print.</strong></p>

<p><strong>Evans, Sara ;M. &#8220;Sons, Daughters, and Patriarchy: Gender and the 1968 Generation.&#8221; <em>The </em></strong><strong><em>American Historical Review</em> 114.2 (2009): 331-47. Print.</strong></p>

<p><strong>Gorfinkel, Elena. “Radley Metzger’s ‘Elegant Arousal’: Taste, Aesthetic Distinction and ;</strong><strong>Sexploitation.” <em>Underground USA: Filmmaking beyond the Hollywood Canon</em>. Ed. Xavier Mendik and Steven Jay. Schneider. London: Wallflower, 2002. 26-39. Print.</strong></p>

<p><strong>Haskell, Molly. &#8220;The Last Decade.&#8221; <em>From Reverence to Rape: The Treatment of Women in the </em></strong><strong><em>Movies</em>. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1974. 323-71. Print.</strong></p>

<p><strong>Henderson, Eric. &#8220;The Alley Cats.&#8221; Rev. of <em>The Alley Cats</em>. <em>Slant Magazine</em> 30 Nov. 2004: n. ;pag. <em>Slant Magazine</em>. Web. 10 Sept. 2012 ;<;<a href="http://www.slantmagazine.com/film/review/the-alley-cats/1268" target="_blank" aria-label="undefined (opens in a new tab)" rel="noreferrer noopener">http://www.slantmagazine.com/film/review/the-alley-cats/1268</a>>;.</strong></p>

<p><strong>Kaplan, Ann. “The Feminist Perspective in Film Studies.” <em>Journal of the University Film </em></strong><strong><em>Association</em>. Vol. 26. Women In Film (1974). 5, 18-20, 22. Print.</strong></p>

<p><strong>Lucas, Tim. &#8220;Lickerish All-sorts.&#8221; <em>Sight &; Sound</em> Nov. 2011: 86. Print.</strong></p>

<p><strong>Mellen, Joan. &#8220;Lesbianism in the Movies.&#8221; <em>Women and Their Sexuality in the New Film.</em> New ;</strong><strong>York: Horizon, 1974. 74-105. Print.</strong></p>

<p><strong>Morris, Gary. &#8220;Seduction Is Universal: Thoughts on Radley Metzger.&#8221; <em>Bright Lights Film Journal</em> 21 (1998): n. pag. <em>Bright Lights Film Journal</em>. Web. 10 Sept. 2012.<;<a href="http://www.brightlightsfilm.com/21/21_metzger.php" target="_blank" aria-label="undefined (opens in a new tab)" rel="noreferrer noopener">http://www.brightlightsfilm.com/21/21_metzger.php</a>>;.</strong></p>

<p><strong>Mulvey, Laura. &#8220;Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.&#8221; <em>Film Theory and Criticism</em>. 7th ed. ;</strong><strong>Oxford: Oxford UP, 2009. 711-22. Print.</strong></p>

<p><strong><em>The Radical Women Manifesto: Socialist Feminist Theory, Program and Organizational </em></strong><strong><em>Structure.</em> Seattle, WA: Red Letter, 1973. Print.</strong></p>

<p><strong>Schaefer, Eric. &#8220;Gauging a Revolution: 16mm Film and the Rise of the Pornographic Feature.&#8221; ;<em>Cinema Journal</em> 41.3 (2002): 3-26. Print.</strong></p>

<p>If you&#8217;d like to read more film essays like this one, consult the <a href="https://philosophyinfilm.com/">Philosophy in Film Homepage</a>!</p>

Metzger’s Women: Gender Representations and Visual Abstraction in ’60s Sexploitation