<p>Contemporary French cinema has seen a rise in the number of female filmmakers, and in turn, an increased focus on feminist perspectives in French film. This is most notable in the “cinema du corps,” a term referring to French films of the 1990’s and 2000’s that are both graphic in their visual representations of the body and oftentimes radical in their ideological assertions. While not all of the films in this group are directed by women, they almost all show an interest in the female body and representations of sexuality. In particular, many of these films harbour ambivalence towards relationships and utilize graphic depictions of both male and female sexuality. Many of the films of Catherine Breillat fit into this categorization, particularly <em>Fat Girl</em> (2001).</p>

<p>The film follows a young, overweight French girl as she tries to cope with her body, her family, and her burgeoning sexuality. This film is a prime example of the cinema du corps, not only for its graphic content, but also its cynical reflections on sexual relations between men and women, and the shamed and confused depictions of female sexuality. Breillat’s <em>Fat Girl</em> (2001) offers a nihilistic reflection on gender relations, using graphic visual representations of rape and female sexuality to explore the tensions formed from these failed relations.</p>

<p>In Breillat’s <em>Fat Girl</em> (2001) a 12-year-old French girl named Anaïs is on vacation with her family. Her older sister, Elena, is skinnier and more attractive than Anaïs, and Elena constantly reminds her of this. Their parents are relatively despondent, but when they do participate in the girls’ lives, it is most often to criticize. They are particularly cruel to Anaïs regarding her weight and eating habits. As the story progresses, the father leaves on business while Elena, who is 15 years old, meets a college-aged boy named Fernando, who convinces Elena that he loves her. One night, while Anaïs lies awake in the same room, Fernando rapes Elena, only to have Elena retrospectively insist that it was consensual and fall deeply in love with him.</p>

<p>Fernando secretly proposes to Elena and gives her an expensive opal ring. Anaïs silently observes their relationship and shares her distrust of Fernando with Elena, but Elena dismisses her and insists that they love each other. Following this conversation, Fernando’s mother comes to the family’s vacation home to retrieve the ring that Fernando stole and gave to Elena. Elena begrudgingly returns the ring, and the family begins the long drive back to their home. While the mother and daughters are sleeping in the car at a rest stop, a wild-looking man breaks the windshield with a hatchet and kills Elena and the mother.</p>

<p>Anaïs, who is awake to witness the attack, gets out of the car and retreats into the woods. The man rapes Anaïs, but halfway through the act, Anaïs seems to acquiesce to his aggression. The man flees, and the police arrive, but Anaïs insists that the man did not rape her. The film ends with Anaïs’s denia,l accompanied by a freeze-frame of her face looking back toward the camera.</p>

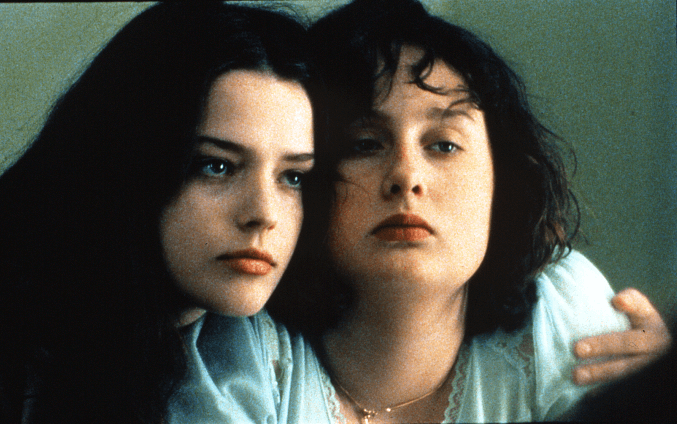

<figure class="wp-block-image aligncenter size-large"><img src="https://philosophyinfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/fat-girl-1200-1200-675-675-crop-000000-1024x576.jpg" alt="Fat Girl (2001)" class="wp-image-1910"/><figcaption class="wp-element-caption"><em>Fat Girl</em> (2001)</figcaption></figure>

<p>While on the surface, Breillat’s <em>Fat Girl</em> (2001) seems like a sad story about a young French girl struggling with her weight and her familial and sexual frustrations, the graphic depictions of these frustrations work to offer a more vivid and complex analysis of female sexuality. For Breillat, the purpose of visualizing rape has greater aspirations than merely shocking the audience; it also works as “a complex representation involving formal strategies that have ideological effects” (Keesey 96). These ideological effects can be seen in the context of the rape, the female victim’s reaction to the rape, and the intention to encourage contradictory and ultimately unsavory identifications on the part of the spectator.</p>

<p>For example, in the first rape scene, which can most accurately be characterized as a “date rape,” the camera looms over the two young lovers as Fernando tries unsuccessfully to have sex with Elena. She is apprehensive and tells him that she is not ready. He becomes frustrated with her repeated rejections and eventually has sex with her anyway. Elena has no choice but to submit to him, and even though she cries and feels guilty afterward, Fernando convinces her that since they are in love, it was all for the best.</p>

<p>This scene is complicated by the potential for contradictory spectator identification. The scene does not offer any formal hints as to which character the spectator is meant to identify or sympathize with. If it is Fernando, then the spectator has no choice but to adopt the guilt of predatory male sexuality acted out on a helpless female victim. His unapologetic advances force the spectator to “adopt a pedophile’s perspective and to participate in his movement toward the object of desire” (Keesey 101). </p>

<p>If it is Elena, then the spectator is made to identify “masochistically with the victim” (Keesey 103). However, there is also the third and most likely option for identification, which is Anaïs. She lies in the corner, acting as the silent voyeur while the rape unfolds in front of her. Just like the spectator, she is forced to watch the rape and powerless to stop it. This scene also reflects Breillat’s concept of passive female desire. Elena willingly removed all of her clothing, indicating to Fernando that she wanted to have sex, only to realize that she was not ready. </p>

<p>Even though Elena insists on waiting to have sex, and Anaïs watches the entire scenario unfold from across the room, neither girl is able to defend Elena’s body against the penetrating male. It is this helplessness that leads to the sense of shame on the part of the female and the uneven power dynamic between the sexuality of the man and the woman. Like many of Breillat’s films, the sexual encounters are often marked by contradictory elements, in this case “desire and shame” and “submission and power” (Gorton 114). While the male uses his power to play out his desires on the female body, the female feels shame and confusion at her own submissive, and ultimately powerless sexuality at the hands of the aggressive, powerful male.</p>

<figure class="wp-block-image aligncenter size-large"><img src="https://philosophyinfilm.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/MV5BNGI1M2MwZmYtYTQwNy00ZmRkLWE4ZDgtNDg0OWM0OGQ5NmUyXkEyXkFqcGdeQXVyNTc0NjY1ODk@._V1_-1024x550.jpg" alt="Fat Girl (2001)" class="wp-image-1911"/><figcaption class="wp-element-caption"><em>Fat Girl </em>(2001)</figcaption></figure>

<p>During Fernando and Elena’s second sexual encounter, which is consensual and regarded by Elena as her “real” first time, the camera focuses on Anaïs’s face. As her sister has sex in the background of the shot, Anaïs lies in bed, turned away from her sister, silently crying. The exact meaning of this emotion is left somewhat ambiguous. She could be crying out of jealousy of her sister’s sexual “success,” or because she knows her sister is being taken advantage of, or even a combination of the two. Despite the ambiguity of Anaïs’s crying, it is obvious that Fernando, and by extension, the power of aggressive male sexuality, is causing pain for both girls. While Elena cries out in physical pain in the background of the shot, Anaïs silently weeps over the pain of Fernando’s presence in their lives.</p>

<p>In the final and most graphic scene of the film, Anaïs is raped by the man who killed Elena and her mother. The surrealist nature of this scene allows for it to be read as a “rape fantasy” in which Anaïs’s identification is split between the attacker and “herself as willing victim, split between the man’s sadism and her own ‘feminine’ masochistic desire to be punished” (Keesey 103). Whether or not this event really takes place or if it is just a fantasy is unclear, but Breillat herself reinforces the notions of a split identification and Anaïs’s desire to be raped, saying that “for girls who have been ‘brought up to be decent,’ rape is the only way to enact their desire for a man…because, following the mindset of our society, they must as it were ‘foist’ the guilt of desire onto the man whom they did not have the power to resist” (Keesey 102). </p>

<p><strong>» You Might Like:</strong><a href="https://philosophyinfilm.com/2014/05/10/responsibility-and-victimization-in-grave-of-the-fireflies/"> </a><a href="https://philosophyinfilm.com/2016/01/06/mixing-genres-and-political-turmoil-in-the-39-steps/">Mixing Genres and Political Turmoil in <em>The 39 Steps</em></a></p>

<p>This reading as a rape fantasy is further legitimized by the conversation that Anaïs and Elena have one night in bed. After Anaïs criticizes Elena for simultaneously idealizing and attempting to erase her first sexual experience with Fernando, Elena claims that she is ultimately glad that her first time was with someone she loved, and that Anaïs is too young to understand. To this Anaïs blandly replies that she hopes her first time is not with someone she loves. She argues that if he doesn’t love her and she doesn’t love him, there can be no disappointment afterward, and the man cannot have the satisfaction of taking advantage of her love.</p>

<p>This scenario that Anaïs describes comes to fruition with the rape at the end of the film. As Anaïs exits the car, the attacker takes notice and slowly walks toward her. She backs away slowly without breaking eye contact with her assailant. In this moment, Anaïs is relatively powerful and unwilling to completely submit to her attacker. As she backs into the woods, the man tackles her and pins her down. She struggles and pleads that he not hurt her, but as he begins to rape her, she suddenly stops struggling. She makes eye contact with him and gently wraps her arms around his neck. Both characters linger for a moment, and then the man leaves. </p>

<p>This is a strange and troubling scenario for the spectator. Not only is it a graphic depiction of the rape of a 12-year-old girl, but it is also a representation of a female embracing her rapist and accepting the role as the submissive object of predatory male desire. Following the rape, although Anaïs does survive, she harbors a similar reaction to that of her sister, by denying that the rape ever happened. This repeated denial reflects the guilt and shame that Anaïs feels about her sexual desires: she theoretically experienced her ideal first sexual encounter (a sexual encounter free of love), but she feels ashamed of her own desires and her submission to male power.</p>

<p>All three sexual encounters of the film, and the subsequent reactions that the female characters have to them, reflect a nihilistic attitude toward gender relations. Elena is raped, humiliated, and then dumped. Anaïs is forced to witness her sister’s rape and the murder of her sister and mother, and is then raped by their killer. Even though both girls are victims at the hands of powerful men, they feel shame. Elena’s shame stems from being tricked into having sex and then left to feel guilty for indulging her sexual desires. Anaïs’s shame comes from her fantasy of rape and her complete submission to the rapist. In both scenarios, the sexual relations (and, by extension, <em>all</em> intimate relations) between men and women are doomed to fail. Both Elena and Anaïs recognize this failure and come to realize that between men and women, intimacy will always be “violently rejected” (Gorton 121). In this way, Breillat’s film works as a feminist critique of traditional gender roles and heteronormative relations between men and women.</p>

<p>However, there is a strong case for seeing <em>Fat Girl</em> (2001), and other “feminist” films from Catherine Breillat, as actually working against feminist ideals, namely insofar as they perpetuate the notion of the female body as an object for the male gaze. One could further argue that these films do not operate well as feminist works because of their excessive reliance on pornographic, often violently sexual depictions of the female body. While it cannot be ignored that <em>Fat Girl</em> (2001) and other Breillat films, such as <em>Romance</em> (1999) and <em>Anatomy of Hell</em> (2004), rely on these unsettling graphic representations, it is actually the intensely graphic nature of these films that forces an awareness of their feminist message. </p>

<p>First, the scenes featuring sex are too unsettling to provide any sexual appeal to the mass audience. However, at the time of its release, censorship boards were worried that the representations of rape in the film (particularly because the victims are young girls) would serve to titillate and even encourage potential rapists and pedophiles (Keesey 101). Breillat herself sees this concern as an attempt to censor the bodies of young females and perpetuate the ideals of a “masculinist social system that stigmatizes the female victims of rape and their bodies rather than attending to the male perpetrators and their violent desires” (Keesey 101). Second, by making the rape scenes so violent and unappealing to the vast majority of male viewers, Breillat “upsets the viewer and unsettles the possibility of watching her film for entertainment only” (Gorton 119). By reducing or even eliminating the entertainment value of her films, Breillat forces the spectator to engage with the images as ideological representations rather than mere titillations.</p>

<p>While Catherine Breillat’s <em>Fat Girl</em> (2001) is very graphic and divisive among theorists and mass audiences alike, it is also unapologetic in its rejection of male/female gender relations as a viable option for women. By limiting the female characters&#8217; choices to rape and sadomasochistic fantasy, the director shows the unappealing nature of these relations and portrays female sexuality, insofar as it is determined by the patriarchal society that it exists in, as confused and shameful. By the end of the film, women are either killed or reduced to being ashamed of their own sexuality and victimhood at the hands of men, and any sexual intimacy between men and women only serves to further subjugate women within the male-dominated power structure, thus making these relations ultimately unsustainable.</p>

<p><strong>Gorton, Kristyn. &#8220;</strong><a href="https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1386/seci.4.2.111_1" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener"><strong>The Point of View of Shame&#8221;: Re-viewing Female Desire in Catherine</strong> <strong>Breillat&#8217;s <em>Romance</em> (1999) and <em>Anatomy of Hell</em> (2004)</strong></a><strong>.&#8221; <em>Studies in European Cinema</em> 4.2 (2007): 111-24. Print.</strong></p>

<p><strong>Keesey, Douglas. &#8220;</strong><a href="https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Split-identification%3A-Representations-of-rape-in-A-Keesey/dcbc6bf71a402aa050ed5e11fc3121404ddbc40c?p2df" target="_blank" rel="noreferrer noopener"><strong>Split Identification: Representations of Rape in Gaspar Noe&#8217;s</strong> <strong><em>Irreversible</em> and Catherine Breillat&#8217;s <em>A Ma Soeur!/Fat Girl</em></strong></a><strong>.&#8221; <em>Studies in European Cinema</em> 7.2 (2010): 95-107. Print.</strong></p>

<p>For more essays like this one, check out the ;<a href="https://philosophyinfilm.com/">Philosophy in Film Homepage</a>!</p>

Gender and Sexuality in Breillat’s Fat Girl (2001)